Hand in reading logs

Staple them in order, and write

What songs would you choose to go with Act 3?

Making connections...

Find a passage/soliloquy/single lines in Act 3...

Brainstorm three songs that you think have a connection between could be paired with themes and quotes songs. Three songs which have some thematic overlap with Act 3.

Left hand column Right Hand Column

Lyrics from song Quotes from Hamlet

(and artist and song title)

HW: (10 points completions grade - typed as either a paragraph or double entry journal) Find 3 more connection to Hamlet... a combination of either literary (poems/novels/short stories, etc) or musical connections (lyrics) that you feel relate to some theme in Hamlet that personally resonates with you, perhaps touching a topic you might write about. Identify the song and artist, share a key stanza, a related quote from Hamlet, and a brief explanation of the connection you see. Again, you can do this double-column entry style (Lyrics in left hand column/ Hamlet lines and explanation of connection in the right hand column) or in another format, just make sure that you provide all of the requested content.

Tomorrow we will share some of our group connections with one other group and watch Act 3.

Thursday: We will have a 30 question/30 point quiz on Act 3: You need to know the plot characters and be able to identify who spoke certain original lines in the play

Tuesday, January 31, 2017

Monday, January 30, 2017

Exchange logs with someone who has not yet read one of your logs...Respond to their log with a comment or question. Print and sign your name.

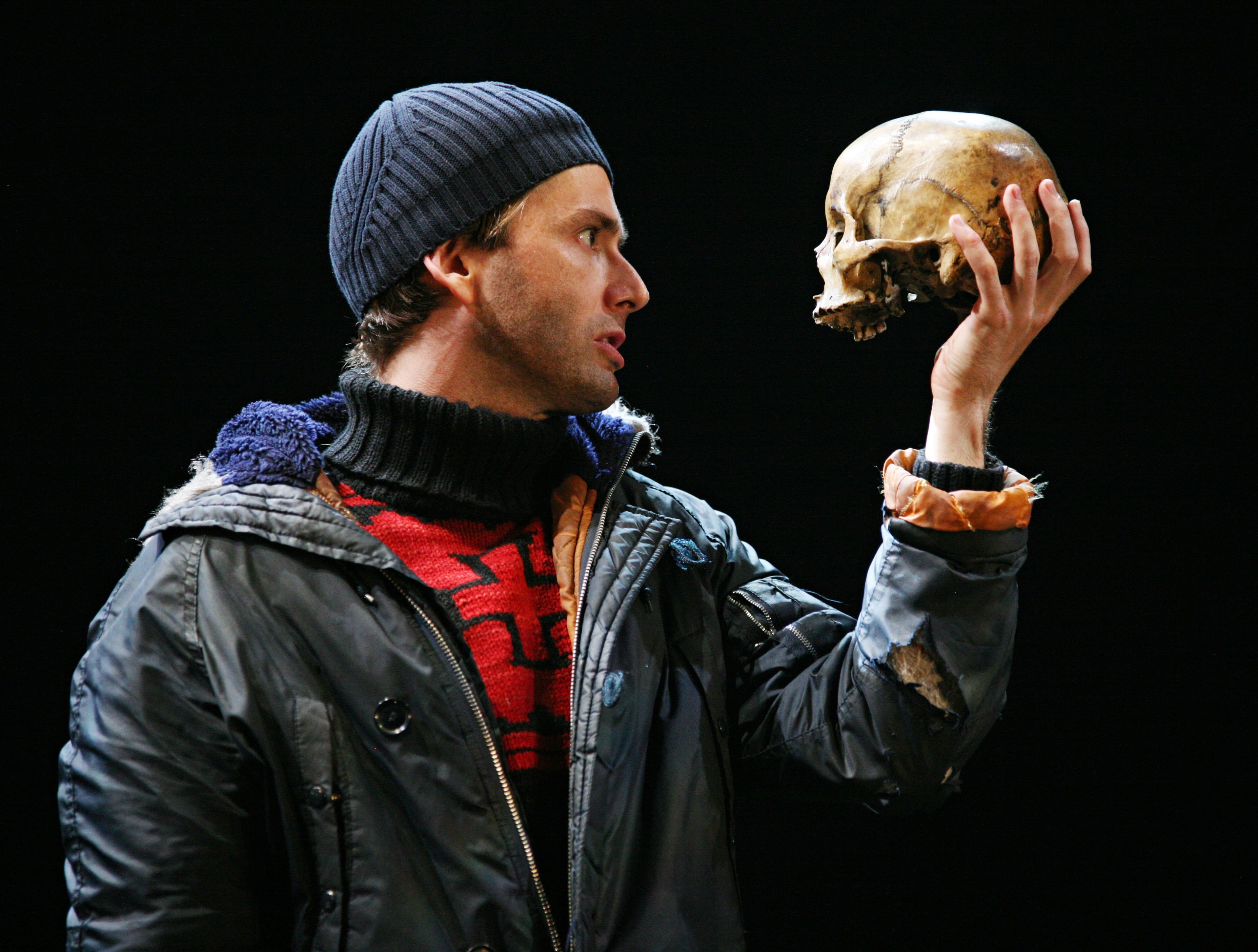

Watch different versions of "To Be or Not To Be"

What differences do you note in the setting? The actor's appearance? The delivery of the lines vocally and physically?

Watch different versions of the nunnery scene.

What differences do you note in the setting and acting?

Read Act 3.3-4 for homework and do log # 10. I will collect the logs tomorrow

Watch different versions of "To Be or Not To Be"

What differences do you note in the setting? The actor's appearance? The delivery of the lines vocally and physically?

Watch different versions of the nunnery scene.

What differences do you note in the setting and acting?

Read Act 3.3-4 for homework and do log # 10. I will collect the logs tomorrow

Friday, January 27, 2017

Wednesday, January 25, 2017

Hamlet...To be or not to be...

1984 #1 book on Amazon.com

1984 is # 1 book after Trump's "alternative facts"

Thursday: Watch and discuss different "O, what a rogue" soliloquies

"To be or not to be..."

With a partner/partners, divide the soliloquy as if it were two voices debating. We want to show the different sides of an internal debate. Are there any lines (or groups of lines) which you feel could/should be read simultaneously by both readers?

After you mark it up for the two sides of the argument, read it aloud with your partner, talk to another group about how they divided the lines.

Now get on your feet and perform your script for one another, trying to convey the sense of a subdued but heavy debate.

Adding acting notes for tone and non-verbal actions: Now, as a group of four, do one more read and script mark-up, preparing as if you were going to be acting the scene. Where would you add notes to guide your voice and your body language and facial expresions? Write notes in the margin to pause, raise your voice, change your tone, gesticulate with your hands, stand up, sit down, throw a fist, clutch your head, etc.

Tomorrow, you will perform for one other group using vocal and physical moves to more fully convey the nuances of Hamlet's internal conflict.

Also tomorrow....

Two groups as far away from one another as we can manage...

Adjust pitch, tone, inflection, and stress to emphasize the meaning of the words and lines and to read in unison as if each of the two groups were one voice.

When the groups finish practicing, face each other and read their parts loudly and angrily to the other group. While this is going on, I will record the debate.

Let's listen to it on the phone

Explore antitheses and what it reveals about Hamlet's state of mind

Watch three different versions of speech

Homework:

Read Act 3.2.1-175

"Ha Ha! Are you honest? "

"Get thee to a nunnery!"

and do Reading Log #8

1984 is # 1 book after Trump's "alternative facts"

Thursday: Watch and discuss different "O, what a rogue" soliloquies

"To be or not to be..."

With a partner/partners, divide the soliloquy as if it were two voices debating. We want to show the different sides of an internal debate. Are there any lines (or groups of lines) which you feel could/should be read simultaneously by both readers?

After you mark it up for the two sides of the argument, read it aloud with your partner, talk to another group about how they divided the lines.

Now get on your feet and perform your script for one another, trying to convey the sense of a subdued but heavy debate.

Adding acting notes for tone and non-verbal actions: Now, as a group of four, do one more read and script mark-up, preparing as if you were going to be acting the scene. Where would you add notes to guide your voice and your body language and facial expresions? Write notes in the margin to pause, raise your voice, change your tone, gesticulate with your hands, stand up, sit down, throw a fist, clutch your head, etc.

Tomorrow, you will perform for one other group using vocal and physical moves to more fully convey the nuances of Hamlet's internal conflict.

Also tomorrow....

Two groups as far away from one another as we can manage...

Adjust pitch, tone, inflection, and stress to emphasize the meaning of the words and lines and to read in unison as if each of the two groups were one voice.

When the groups finish practicing, face each other and read their parts loudly and angrily to the other group. While this is going on, I will record the debate.

Let's listen to it on the phone

Explore antitheses and what it reveals about Hamlet's state of mind

Watch three different versions of speech

Homework:

Read Act 3.2.1-175

"Ha Ha! Are you honest? "

"Get thee to a nunnery!"

and do Reading Log #8

To Be or Not To Be Hamlet 3.1

Quiz on Acts 1 and 2:

Complete reading of Hamlet personal essay example #1

View "Oh,what a rogue" scenes

HW: Read 3.1 (To be or not to be) and do reading log # 7

Monday, January 23, 2017

Share (with reading log # 5 (first half of 2.2 - this weekend) and 6 (second half of 2.2 - last night); exchange and briefly comment with two other classmates (one for reading log # 5 and another classmate for reading log #6)

Finish reading the second half of the Hamlet Personal Connection Paper assignment and example essay (see below)

For example, the issue of betrayal is a significant issue in the text and exists from the beginning of the play to the end of the play. There are so many moments where characters feel they have been betrayed, where they feel their trust has been abused, where they feel used and hurt by those who professed to love and honor them. Your job would be to think about betrayal then. Define it. Try to break open this topic and see how many directions you might take it. Gather up as many citations as you can on the subject. Think about what the subject means to you. Think about how the issue of betrayal exists in our country, in our world, in your community, in your school. Contemplate. Write about it. Any songs on the subject? Any poems on the subject? Have you seen any films on the subject? Historical events? Bring some of these references in. Make some allusions. Is one kind of betrayal worse than another kind? What does Shakespeare present about the issue? What do you think about the issue through his language? How can you think more deeply about the subject by considering some of his lines/passages and some of the events from the play? How do things work out? Any lessons learned? Any wisdom gained?

Create paragraphs as you would for any paper….around key angles/sub-points of your issue. Include several citations from the play in each paragraph.

Demonstrate your own style as a writer: I encourage you to try employing two or three literary/rhetorical devices: below are some suggestions.

Metaphors

Allusions

Repetition

Rhetorical Questions

|

Simile

Anecdote

Parallel Structure

Personification

Alliteration

|

Knowledge of the play: Citations should not be just dropped into your paper but should be explained and discussed, shared and integrated into your sentences. You need to demonstrate your knowledge of the play….you should reference what happens and you should make reference to characters and their feelings/beliefs/behaviors. You should have 4-8 citations in your paper. Be sure that their relevance to your point is clear.

Example Essay

Here is an example of a personal response to Hamlet written by Meghan O'Rourke for Slate Magazine. The link is provided here: http://www.slate.com/articles/life/grieving/features/2011/the_long_goodbye/hamlets_not_depressed_hes_grieving.html

The Long Goodbye: Hamlet’s Not Depressed, He’s Grieving

By Maghan O’Rourke

I had a hard time sleeping right after my mother died. The nights were long and had their share of what C.S. Lewis, in his memoir A Grief Observed, calls "mad, midnight … entreaties spoken into the empty air." One of the things I did was read. I read lots of books about death and loss. But one said more to me about grieving than any other: Hamlet. I'm not alone in this. A colleague recently told me that after his mother died he listened over and over to a tape recording he'd made of the Kenneth Branagh film version.

I had always thought of Hamlet's melancholy as existential. I saw his sense that "the world is out of joint" as vague and philosophical. He's a depressive, self-obsessed young man who can't stop chewing at big metaphysical questions. But reading the play after my mother's death, I felt differently. Hamlet's moodiness and irascibility suddenly seemed deeply connected to the fact that his father has just died, and he doesn't know how to handle it. He is radically dislocated, stumbling through the world, trying to figure out where the walls are while the rest of the world acts as if nothing important has changed. I can relate. When Hamlet comes onstage he is greeted by his uncle with the worst question you can ask a grieving person: "How is it that the clouds still hang on you?" It reminded me of the friend who said, 14 days after my mother died, "Hope you're doing well." No wonder Hamlet is angry and cagey.

Hamlet is the best description of grief I've read because it dramatizes grief rather than merely describing it. Grief, Shakespeare understands, is a social experience. It's not just that Hamlet is sad; it's that everyone around him is unnerved by his grief. And Shakespeare doesn't flinch from that truth. He captures the way that people act as if sadness is bizarre when it is all too explainable. Hamlet's mother, Gertrude, tries to get him to see that his loss is "common." His uncle Claudius chides him to put aside his "unmanly grief." It's not just guilty people who act this way. Some are eager to get past the obvious rawness in your eyes or voice; why should they step into the flat shadows of your "sterile promontory"? Even if they wanted to, how could they? And this tension between your private sadness and the busy old world is a huge part of what I feel as I grieve—and felt most intensely in the first weeks of loss. Even if, as a friend helpfully pointed out, my mother wasn't murdered.

I am also moved by how much in Hamlet is about slippage—the difference between being and seeming, the uncertainty about how the inner translates into the outer. To mourn is to wonder at the strangeness that grief is not written all over your face in bruised hieroglyphics. And it's also to feel, quite powerfully, that you're not allowed to descend into the deepest fathom of your grief—that to do so would be taboo somehow. Hamlet is a play about a man whose grief is deemed unseemly.

Strangely, Hamlet somehow made me feel it was OK that I, too, had "lost all my mirth." My colleague put it better: "Hamlet is the grief-slacker's Bible, a knowing book that understands what you're going through and doesn't ask for much in return," he wrote to me. Maybe that's because the entire play is as drenched in grief as it is in blood. There is Ophelia's grief at Hamlet's angry withdrawal from her. There is Laertes' grief that …(Mr. Wesley deleted the spoiler part of the sentence). There is Gertrude and Claudius' grief, which is as fake as the flowers in a funeral home. Everyone is sad and messed up. If only the court had just let Hamlet feel bad about his dad, you start to feel, things in Denmark might not have disintegrated so quickly!

Hamlet also captures one of the aspects of grief I find it most difficult to speak about—the profound sense of ennui, the moments of angrily feeling it is not worth continuing to live. After my mother died, I felt that abruptly, amid the chaos that is daily life, I had arrived at a terrible, insistent truth about the impermanence of the everyday. Everything seemed exhausting. Nothing seemed important. C.S. Lewis has a great passage about the laziness of grief, how it made him not want to shave or answer letters. At one point during that first month, I did not wash my hair for 10 days. Hamlet's soliloquy captures that numb exhaustion, and now I read it as a true expression of grief:

O that this too too sullied flesh would melt,

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew,

Or that the Everlasting had not fix'd

His canon 'gainst self-slaughter. O God! God!

How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world!

Those adjectives felt apt. And so, even, does the pained wish—in my case, thankfully fleeting—that one might melt away. Researchers have found that the bereaved are at a higher risk for suicideality (or suicidal thinking and behaviors) than the depressed. For many, that risk is quite acute. For others of us, this passage captures how passive a form those thoughts can take. Hamlet is less searching for death actively than he is wishing powerfully for the pain just to go away. And it is, to be honest, strangely comforting to see my own worst thoughts mirrored back at me—perhaps because I do not feel likely to go as far into them as Hamlet does.

The way Hamlet speaks conveys his grief as much as what he says. He talks in run-on sentences to Ophelia. He slips between like things without distinguishing fully between them—"to die, to sleep" and "to sleep, perchance to dream." He resorts to puns because puns free him from the terrible logic of normalcy, which has nothing to do with grief and cannot fully admit its darkness.

And Hamlet's madness, too, makes new sense. He goes mad because madness is the only method that makes sense in a world tyrannized by false logic. If no one can tell whether he is mad, it is because he cannot tell either. Grief is a bad moon, a sleeper wave. It's like having an inner combatant, a saboteur who, at the slightest change in the sunlight, or at the first notes of a jingle for a dog food commercial, will flick the memory switch, bringing tears to your eyes. No wonder Hamlet said, "… for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so." Grief can also make you feel, like Hamlet, strangely flat. Nor is it ennobling, as Hamlet drives home. It makes you at once vulnerable and self-absorbed, needy and standoffish, knotted up inside, even punitive.

Like Hamlet, I, too, find it difficult to remember that my own "change in disposition" is connected to a distinct event. Most of the time, I just feel that I see the world more accurately than I used to. ("There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,/ Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.") Pessimists, after all, are said to have a more realistic view of themselves in the world than optimists.

The other piece of writing I have been drawn to is a poem by George Herbert called "The Flower." It opens:

How Fresh, O Lord, how sweet and clean

Are thy returns! ev'n as the flowers in spring;

To which, besides their own demean,

The late-past frosts tributes of pleasure bring.

Grief melts away

Like snow in May,

As if there were no such cold thing.

Who would have thought my shrivel'd heart

Could have recover'd greennesse? It was gone

Quite under ground; as flowers depart

To see their mother-root, when they have blown;

Where they together

All the hard weather,

Dead to the world, keep house unknown.

Quite underground, I keep house unknown: It does seem the right image of wintry grief. I look forward to the moment when I can say the first sentence of the second stanza and feel its wonder as my own.

Meghan O'Rourke is Slate's culture critic and an advisory editor. She was previously an editor at The New Yorker. The Long Goodbye, a memoir about her mother's death, is now out in paperback.

1st period; left off at 57 minute mark

7th period; still at 49 minute mark

“O,

What a Rogue” Soliloquy lesson

2.2.576-634 (pp 117-119)

Sit in a circle and read the speech round-robin, each

student reading only to a semicolon, period, question mark, or exclamation

point.

After reading, circle or underline difficult words,

and consult notes on the facing pages.

Ask questions and answer them as a group, making sure

your group has a good sense of the speech.

Group Discussion Leader (s): Alternate leading

discussion of the questions below:

1. It

is obvious to the audience or reader that Hamlet is alone onstage. What else, then, could he mean when he

begins, “Now I am alone?”

2. Why

is the Prince calling himself a “rogue” and a “peasant slave”?

3. Hamlet

compares himself to the player (an

actor). What does this comparison reveal

about Hamlet’s self-perception?

4. Throughout

the play, much violence is done to ears.

How does Hamlet’s “cleave the general ear” relate to other “ear”

references?

5. Hamlet

uses a lot of theatrical terminology in his speech. Find some examples. Why might Hamlet be thinking in theatrical

terms?

6. Find

lines or phrases that explain why Hamlet thinks himself a coward. Do you think he is a coward, or he is acting

cautiously by looking for external evidence to prove Claudius’ guilt?

What does a visual element add to our understanding of the speech? Does it help? How? What do the tonal elements add? How does the actor's use of stress, inflection, and pauses affect your understanding?

HW: Review Acts 1 and 2: Quiz tomorrow...pretty comprehensive...35 questions/35 points...know the characters and plot

Hamlet:

Introduce the Hamlet self-reflection essay...

1st period; left off at 42 minute mark

7th period; still at 28 minute mark

This weekend you read 2.2.1-403.

Watch to 57th minute

Today...Themes for self-reflection...

Read aloud pages 99-101

2.2.261-334

Life or situations as a "prison"

Sadness turning all things ugly

perception changes reality - even the majesty of earth and man seems ...like nothing, when we are grieving or depressed

Man as majestic

Denmark's a prison (page 99) and nothing is either good or bad but thinking makes it so...

HW: Finish reading 2.2 and do log # 6

Pay particular attention to "O 'what a rogue is man 2.2.576-635" soliloquy

Introduce the Hamlet self-reflection essay...

English IV AP

Hamlet Paper

Points:

150

Due Date: February 18, 2017

Pages: 1.5 to 2.0 pages, single-spaced,

12 font

Personal

Insights and Analysis Paper

This paper is a creative insight

paper, a first person paper in which

you examine an issue from Hamlet which is meaningful for you and is written

from your personal perspective.

Explain how the issue is important,

thought provoking, meaningful, for you, in today’s world while also providing

evidence and knowledge of how this topic is treated in the play.

Your essay, while containing

personal insights and connections, should also reveal a thoughtful

understanding/analysis of Shakespeare’s treatment of that topic in Hamlet - complete with citations that

are integrated nicely into your own well crafted sentences, citations that are

explained and honored.

Your job is to be contemplative in

nature, to discuss how Shakespeare presents this issue, in all its complexity.

To show the complexity of the issue, you are to focus on one issue and track it, trace it, build it, apply it to yourself,

to the world you live in. The issue

should be complex enough to allow for a thorough discussion.

Some

topics you might consider:

The difficulty of finding loyal

friends

Honoring the requests of parents

Relationships with parents

Relationships with friends

Grief: what is it like to grieve the

loss of a loved one

Finding meaning and purpose in the

world

The difficulty of making a decision

The tension between thought and

action

The nature of betrayal

Fate: what is said about this?

Death: the mystery of death…the

undiscovered country

man’s relation to evil forces

The desire for perfection

Desire for love and connection

Desire for wholeness

Fears

Ethical dilemmas we face

Our relationship to God

Our reaction to injustice

One’s capacity for love

One’s relationship with friends,

with family

Human’s immortality/the soul

The fear of death

The desire for virtue

Our desire to please God

Our desire to please family

The nature of grief

For

example, the issue of betrayal is a

significant issue in the text and exists from the beginning of the play to the

end of the play. There are so many moments where characters feel they have been

betrayed, where they feel their trust has been abused, where they feel used and

hurt by those who professed to love and honor them. Your job would be to think

about betrayal then. Define it. Try to break

open this topic and see how many directions you might take it. Gather up as

many citations as you can on the subject. Think about what the subject means to

you. Think about how the issue of betrayal exists in our country, in our world,

in your community, in your school. Contemplate.

Write about it. Any songs on the subject? Any poems on the subject? Have you

seen any films on the subject? Historical events? Bring some of these

references in. Make some allusions. Is one kind of betrayal worse than another

kind? What does Shakespeare present about the issue? What do you think about

the issue through his language? How can you think more deeply about the subject

by considering some of his lines/passages and some of the events from the play?

How do things work out? Any lessons learned? Any wisdom gained?

Create

paragraphs as you would for any paper….around

key angles/sub-points of your issue. Include several citations from the play in

each paragraph.

Demonstrate

your own style as a writer: I encourage you to try employing two or three

literary/rhetorical devices: below are some suggestions.

Metaphors

Allusions

Repetition

Rhetorical Questions

|

Simile

Anecdote

Parallel Structure

Personification

Alliteration

|

Knowledge

of the play: Citations should not be just

dropped into your paper but should be explained and discussed, shared and

integrated into your sentences. You need to demonstrate your knowledge of the

play….you should reference what happens and you should make reference to characters

and their feelings/beliefs/behaviors. You

should have 4-8 citations in your paper.

Be sure that their relevance to your point is clear.

Example

Essay

Here is an example of a personal

response to Hamlet written by Meghan

O'Rourke for Slate Magazine. The link is provided here: http://www.slate.com/articles/life/grieving/features/2011/the_long_goodbye/hamlets_not_depressed_hes_grieving.html

The

Long Goodbye: Hamlet’s Not Depressed, He’s Grieving

By Maghan O’Rourke

I had a hard time sleeping right

after my mother died. The nights were long and had their share of what C.S.

Lewis, in his memoir A Grief Observed, calls "mad, midnight … entreaties

spoken into the empty air." One of the things I did was read. I read lots

of books about death and loss. But one said more to me about grieving than any

other: Hamlet. I'm not alone in this. A colleague recently told me that after

his mother died he listened over and over to a tape recording he'd made of the

Kenneth Branagh film version.

I had always thought of Hamlet's

melancholy as existential. I saw his sense that "the world is out of

joint" as vague and philosophical. He's a depressive, self-obsessed young

man who can't stop chewing at big metaphysical questions. But reading the play

after my mother's death, I felt differently. Hamlet's moodiness and

irascibility suddenly seemed deeply connected to the fact that his father has

just died, and he doesn't know how to handle it. He is radically dislocated,

stumbling through the world, trying to figure out where the walls are while the

rest of the world acts as if nothing important has changed. I can relate. When

Hamlet comes onstage he is greeted by his uncle with the worst question you can

ask a grieving person: "How is it that the clouds still hang on you?"

It reminded me of the friend who said, 14 days after my mother died, "Hope

you're doing well." No wonder Hamlet is angry and cagey.

Hamlet is the best description of

grief I've read because it dramatizes grief rather than merely describing it.

Grief, Shakespeare understands, is a social experience. It's not just that

Hamlet is sad; it's that everyone around him is unnerved by his grief. And

Shakespeare doesn't flinch from that truth. He captures the way that people act

as if sadness is bizarre when it is all too explainable. Hamlet's mother,

Gertrude, tries to get him to see that his loss is "common." His

uncle Claudius chides him to put aside his "unmanly grief." It's not

just guilty people who act this way. Some are eager to get past the obvious

rawness in your eyes or voice; why should they step into the flat shadows of

your "sterile promontory"? Even if they wanted to, how could they?

And this tension between your private sadness and the busy old world is a huge

part of what I feel as I grieve—and felt most intensely in the first weeks of

loss. Even if, as a friend helpfully pointed out, my mother wasn't murdered.

I am also moved by how much in

Hamlet is about slippage—the difference between being and seeming, the

uncertainty about how the inner translates into the outer. To mourn is to

wonder at the strangeness that grief is not written all over your face in

bruised hieroglyphics. And it's also to feel, quite powerfully, that you're not

allowed to descend into the deepest fathom of your grief—that to do so would be

taboo somehow. Hamlet is a play about a man whose grief is deemed unseemly.

Strangely, Hamlet somehow made me feel

it was OK that I, too, had "lost all my mirth." My colleague put it

better: "Hamlet is the grief-slacker's Bible, a knowing book that

understands what you're going through and doesn't ask for much in return,"

he wrote to me. Maybe that's because the entire play is as drenched in grief as

it is in blood. There is Ophelia's grief at Hamlet's angry withdrawal from her.

There is Laertes' grief that …(Mr. Wesley deleted the spoiler part of the

sentence). There is Gertrude and Claudius' grief, which is as fake as the

flowers in a funeral home. Everyone is sad and messed up. If only the court had

just let Hamlet feel bad about his dad, you start to feel, things in Denmark

might not have disintegrated so quickly!

Hamlet also captures one of the

aspects of grief I find it most difficult to speak about—the profound sense of

ennui, the moments of angrily feeling it is not worth continuing to live. After

my mother died, I felt that abruptly, amid the chaos that is daily life, I had

arrived at a terrible, insistent truth about the impermanence of the everyday.

Everything seemed exhausting. Nothing seemed important. C.S. Lewis has a great

passage about the laziness of grief, how it made him not want to shave or

answer letters. At one point during that first month, I did not wash my hair

for 10 days. Hamlet's soliloquy captures that numb exhaustion, and now I read

it as a true expression of grief:

O that this too too sullied flesh

would melt,

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew,

Or that the Everlasting had not

fix'd

His canon 'gainst self-slaughter. O

God! God!

How weary, stale, flat, and

unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this

world!

Those adjectives felt apt. And so,

even, does the pained wish—in my case, thankfully fleeting—that one might melt

away. Researchers have found that the bereaved are at a higher risk for

suicideality (or suicidal thinking and behaviors) than the depressed. For many,

that risk is quite acute. For others of us, this passage captures how passive a

form those thoughts can take. Hamlet is less searching for death actively than

he is wishing powerfully for the pain just to go away. And it is, to be honest,

strangely comforting to see my own worst thoughts mirrored back at me—perhaps

because I do not feel likely to go as far into them as Hamlet does.

The way Hamlet speaks conveys his

grief as much as what he says. He talks in run-on sentences to Ophelia. He

slips between like things without distinguishing fully between them—"to

die, to sleep" and "to sleep, perchance to dream." He resorts to

puns because puns free him from the terrible logic of normalcy, which has

nothing to do with grief and cannot fully admit its darkness.

And Hamlet's madness, too, makes new

sense. He goes mad because madness is the only method that makes sense in a

world tyrannized by false logic. If no one can tell whether he is mad, it is

because he cannot tell either. Grief is a bad moon, a sleeper wave. It's like

having an inner combatant, a saboteur who, at the slightest change in the

sunlight, or at the first notes of a jingle for a dog food commercial, will

flick the memory switch, bringing tears to your eyes. No wonder Hamlet said,

"… for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it

so." Grief can also make you feel, like Hamlet, strangely flat. Nor is it

ennobling, as Hamlet drives home. It makes you at once vulnerable and

self-absorbed, needy and standoffish, knotted up inside, even punitive.

Like Hamlet, I, too, find it

difficult to remember that my own "change in disposition" is

connected to a distinct event. Most of the time, I just feel that I see the

world more accurately than I used to. ("There are more things in heaven

and earth, Horatio,/ Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.") Pessimists,

after all, are said to have a more realistic view of themselves in the world

than optimists.

The other piece of writing I have

been drawn to is a poem by George Herbert called "The Flower." It

opens:

How Fresh, O Lord, how sweet and

clean

Are thy returns! ev'n as the flowers

in spring;

To which, besides their own demean,

The late-past frosts tributes of

pleasure bring.

Grief melts away

Like snow in May,

As if there were no such cold thing.

Who would have thought my shrivel'd

heart

Could have recover'd greennesse? It

was gone

Quite under ground; as flowers depart

To see their mother-root, when they

have blown;

Where they together

All the hard weather,

Dead to the world, keep house unknown.

Quite underground, I keep house

unknown: It does seem the right image of wintry grief. I look forward to the

moment when I can say the first sentence of the second stanza and feel its

wonder as my own.

Meghan

O'Rourke is Slate's culture critic and an advisory editor. She was previously

an editor at The New Yorker. The Long Goodbye, a memoir about her mother's

death, is now out in paperback.

1st period; left off at 42 minute mark

7th period; still at 28 minute mark

This weekend you read 2.2.1-403.

Watch to 57th minute

Today...Themes for self-reflection...

Read aloud pages 99-101

2.2.261-334

Life or situations as a "prison"

Sadness turning all things ugly

perception changes reality - even the majesty of earth and man seems ...like nothing, when we are grieving or depressed

Man as majestic

Denmark's a prison (page 99) and nothing is either good or bad but thinking makes it so...

HW: Finish reading 2.2 and do log # 6

Pay particular attention to "O 'what a rogue is man 2.2.576-635" soliloquy

Thursday, January 19, 2017

Hamlet 2.1

Miming Madness?

Pantomime what isn't seen in 2.1.84-134.

Groups of three...

One student will read the lines while the other students mime the prescribed actions, including adjustments to clothing.

What is Hamlet up to in this scene?

Why is he treating Ophelia this way?

Does he love Ophelia?

Pantomime what isn't seen in 2.1.84-134.

Groups of three...

One student will read the lines while the other students mime the prescribed actions, including adjustments to clothing.

What is Hamlet up to in this scene?

Why is he treating Ophelia this way?

Does he love Ophelia?

If so, what possible reasons could he have for acting this way towards her?

What about Ophelia - does she love Hamlet? What is her reaction to his behavior? Try to pinpoint her emotions.

Remember, Hamlet wears the guise of madness so that no one suspects him of trying to plot his revenge to avenge his father's murder.

HW: This weekend, read 2.2.1-403 (pp and do reading log # 5)

Reading log sharing

Read Aloud 2.1.1-83

Circle words and phrases that reveal Polonius's values.

What do you think they reveal about Polonius's values?

What are several character traits we can infer from his words and behaviour?

It takes one to know one? What do you think Polonius might have been like as a young man?

Pantomime what isn't seen in 2.1.84-134.

Groups of three...

One student will read the lines while the other students mime the prescribed actions, including adjustments to clothing.

What is Hamlet up to in this scene?

Why is he treating Ophelia this way?

Does he love Ophelia?

Read Aloud 2.1.1-83

Circle words and phrases that reveal Polonius's values.

What do you think they reveal about Polonius's values?

What are several character traits we can infer from his words and behaviour?

It takes one to know one? What do you think Polonius might have been like as a young man?

Pantomime what isn't seen in 2.1.84-134.

Groups of three...

One student will read the lines while the other students mime the prescribed actions, including adjustments to clothing.

What is Hamlet up to in this scene?

Why is he treating Ophelia this way?

Does he love Ophelia?

Tuesday, January 17, 2017

Friday, January 13, 2017

With a partner, read aloud Hamlet's Soliloquy (alternating every two

lines) and then answer # 6;

Discuss questions 1, 2, 3 and 5 in groups of four. One person leads the discussion of each respective question, seeking input from each member of the group.

Watch Hamlet Act 1, scenes 1-2

Homework: Read Act 1, Scenes 3 & 4 and do reading log # 3

Wednesday, January 11, 2017

Hamlet Day 3 Act 1.2 logs # 2 & 3

January 12, 2017

Reading Log # 2 (a departure from the normal format): In reading scenes 1 and 2 leading up to Hamlet's tortured soliloquy in lines 132-165 of act 2, what situations have you come across which might contribute to Hamlet's stress and despair?

Write a paragraph which explains some reasons that Hamlet is feeling so horrible. Embed two short to three short quotes in your response (properly cited with the the act. scene. line in parentheses at the end of the sentence containing the quote).

Exchange paragraphs with someone near you.

A close reading of Claudius's opening speech in Scene 2

Question or focus prompts

|

Your response (in your own words) and

any supporting textual evidence and/or properly cited lines (act, scene, and

line #’s, e.g., 1.2.40-47)

|

1) A second look at King Claudius’s opening

speech up until he begins addressing Hamlet directly 1.2.1-133

The use of the

royal “we”; usually only used in addressing political matters (“I” is used in

personal matters).

When does Claudius

use “we” (or "our" or "us)?

When does he use

“I”?

What pronoun “we”

or “I” does he use in addressing Hamlet directly? (1.2.90-121)

Why do you think he

uses this particular pronoun rather than the other one?

|

|

2) Antithesis (1.2.9-13): Look for antithesis, the

balancing of two contrasting ideas, words, phrases, or sentences in parallel

grammatical form: “with mirth in funeral and dirge in marriage”, etc. What feelings do these juxtapositions evoke

for you? What feelings do you think Claudius wished to evoke by using them?

Do they match your feelings?

|

|

3) Choice of words: Why

does Claudius remember old King Hamlet with “wisest sorrow” (1.2.6) rather

than “deep sorrow”? Why does he say it

“befitted” (1.2.1) them to bear their “hearts in grief”?

|

|

4) Order of ideas Claudius presents: Although Hamlet’s mourning is of

major concern to Claudius, why does he justify his marriage to Gertrude, deal

with Norway’s impending invasion, and respond to Laertes’ petition before he

addresses Hamlet?

|

|

5) Looking for underlying thoughts of

Hamlet and Claudius

Examine the

exchange between Claudius and Hamlet in 1.2.66-96 (“But now, my cousin Hamlet

and my son” to “To do obsequious sorrow” with an emphasis on understanding

the subtext of each character in this scene.

When Claudius says,

“But now, my cousin Hamlet and my son,” what does he really want? What is he

thinking? Why might he choose a public place to greet Hamlet?

When Hamlet says,

“’Seems,’ madam? Nay, it is. I know not ‘seems’” what does he really mean?

What is he thinking about his mother? Why does Hamlet use puns (like the pun

on “kind” which can mean “affectionate” or “natural and lawful” in line 67,

and the pun on “common” which can mean both “universal occurrence” and “vulgar”

in line 76) and riddles (like his reply in line 69, “Not so my lord. I am too much in the sun,” to Claudius’s

question “How is it that the clouds still hang on you?” when he speaks to

Gertrude and Claudius?

|

|

6) Re-read Hamlet’s soliloquy “O, that this

too, too sullied flesh” (1.2.133-164) a couple of times and try to paraphrase

it with your partner.

What

signals in the language give clues to Hamlet’s innermost thoughts – for

example, choice of words, construction of phrases, sequence of thoughts?

Does

he hide behind puns as he does with Claudius? What does the antithesis

reveal?

|

HW: Complete boxes 1, 2, 3, 5 & 6 and finish reading scene Act 1, scene 2 (lines 165-280)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)